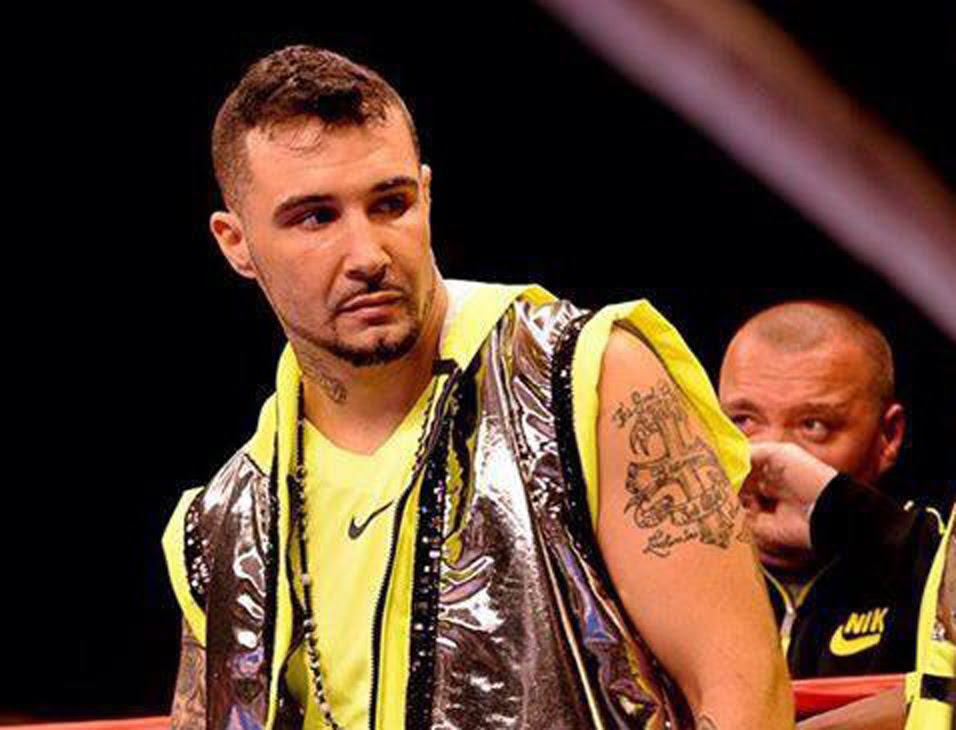

PROVIDENCE, R.I. (March 24th, 2014) – KJ Harrison-Lombardi had hit rock bottom.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. (March 24th, 2014) – KJ Harrison-Lombardi had hit rock bottom.

A once-promising athlete, he had long since given up on boxing, replacing his life in the gym with a far less glamorous life on the streets. His relationship with his girlfriend of more than six years had just gone up in flames, and his relationship with his father, a once inseparable bond that had fizzled through the years after his parents separated, remained icy at best.

Mired in a deep depression, he coped with the pain the only way he knew how.

“I always turned to drugs,” he said, “and I never knew when to stop.”

Six years ago during one of his binges, Harrison-Lombardi did so many drugs – “sixteen and a half grams in two days … and I was using syringes and cocaine at that point” – he started having a seizure late one night while sitting in his mother’s living room.

“The only reason she woke up was because I had my feet on the glass coffee table,” he recalled.

When the paramedics arrived, Harrison-Lombardi had stopped breathing. They gave him an adrenaline shot to his chest and immediately rushed him to the emergency room.

“All I remember from the hospital was opening my eyes slightly, lying there in a cold sweat,” Harrison-Lombardi said. “The first thing my mother said to me was, ‘Don’t ever do it again.’

“To this day, I’ve never used a syringe again in my life.”

Harrison-Lombardi is now drug-free for the first time in nearly a decade, but his road to redemption wasn’t just a straight line from the emergency room following that eventful night six years ago. Even after a near brush with death, the 31-year-old Providence native continued battling his addictions, even up until a year and a half ago while training for his professional boxing debut.

The fact he’s still alive – still chasing his dream in the ring – is a testament to his perseverance and will to live, an immeasurable inner toughness developed, ironically, during his darkest days aimlessly wandering the streets hustling, doing drugs, and not knowing where he’d be sleeping on a nightly basis.

Undefeated at 5-0-1, Harrison-Lombardi will return to the ring Friday, March 28th, 2014 in a four-round middleweight bout on the undercard of Classic Entertainment & Sports’ professional boxing event at Twin River Casino.

“I never understood my purpose until boxing,” he said. “Boxing is what keeps me sober. It’s my natural high.”

________

Growing up in the Smith Hill neighborhood of Providence, Harrison-Lombardi never envisioned a career in boxing. Football was his first love. Fighting was merely a means of self-defense.

“My father always wanted to make sure we could take care of ourselves,” he said.

“I was the only white kid in black neighborhoods, so they tried to test me … until they actually fought me.”

On his father’s advice, Harrison-Lombardi started out taking taekwondo lessons at the age of 8 before moving on to kenpo karate, a stand-up form of martial arts based primarily on counterstrikes.

At 13, he took up boxing at the Phantom Boxing Club under the direction of instructor Artie Artwell and quickly launched his amateur career, even bypassing football several years later as a freshman at East Providence High School so he could continue boxing.

Shortly thereafter, Harrison-Lombardi won the New England Silver Gloves Tournament (ages 10 to 15) before losing in the regional finals at Saratoga Springs, N.Y. He also competed in the N.E. Junior Olympics, where he won the Most Outstanding Boxer award, and fought in the northeast semifinals in Lake Placid, N.Y., losing a 3-2 decision after coming down with a stomach bug the night before the fight.

Despite a successful, four-year run in which he fought 30 times and lost only a handful of fights, Harrison-Lombardi’s father wanted his son to expand his knowledge of the sport, so he brought him to renowned trainer Peter Manfredo Sr.

“Artie was a Philadelphia guy. My father just didn’t know much about him,” Harrison-Lombardi said.

Under Manfredo Sr.’s guidance, Harrison-Lombardi competed in the N.E. Golden Gloves, but lost in the finals, at which point Manfredo Sr. urged the then 18-year-old to consider turning pro.

“He had [his son] Peter [Manfredo Jr.], Matt [Godfrey] and Jason [Estrada] all ready to turn pro,” Harrison-Lombardi said. “He didn’t have time for amateurs, but I didn’t want to turn pro for the sake of turning pro and just half-ass it. I actually lost more when I was with Peter than anything, so I just walked away.

“That’s when everything took a turn for the worse.”

________

With boxing on the backburner, Harrison-Lombardi began playing football again. He was the starting quarterback at East Providence High, even earning All-League honors in his junior year, but trouble was always right around the corner.

Life at home became difficult when his parents separated, which caused his relationship with his father to sour. Harrison-Lombardi soon found himself running the streets at night – partying, doing drugs, and chasing women.

“I kept chasing this relationship with my father that wasn’t there,” he said. “He was raised by a stepdad who drank and beat the [crap] out of him, and so my father would then beat the [crap] out of me. I feared nobody.

“But for all those years, I was lost. Once I got a girlfriend in high school when I was 15, he actually got jealous because I was spending my time with her. He kicked me out when I was a junior. I was too busy being involved in the streets hustling, trying to make money.

“I was 19, 20 years old always worrying about where I was going to sleep.”

As he battled his addictions, he continued dreaming of a better life for himself, a life without drugs, alcohol and drama. Growing up, Harrison-Lombardi first wanted to be a state trooper, then a Navy SEAL. Neither happened, so he joined the U.S. Air Force after graduating high school in 2001, but that dream died quickly, too, when he received a general discharge for poor conduct.

“I would get in trouble for sneaking girls into my dorm, or just leaving the base without a pass,” he recalled.

When he returned home, Harrison-Lombardi went back to playing football, this time in a semi-pro league, but his behavior off the field – the drugs, the partying – didn’t change.

“I could get away with my party life and still play football,” he said, “but you couldn’t do that in boxing.”

Seven years after graduating high school, Harrison-Lombardi found himself in the hospital clinging to a life after a near overdose in his mother’s living room, but not even that was enough to deter him from a life on the streets.

Things didn’t begin to change until two years later when Harrison-Lombardi’s younger brother, 16 at the time, told him he wanted to compete in mixed martial arts. Harrison-Lombardi brought him to Tri Force Academy in Pawtucket, which happened to be located in the same building as Manfredo’s Gym, where Harrison-Lombardi had spent many afternoons and nights as a promising amateur.

“The place smelled the same and everything,” Harrison-Lombardi said. “Peter [Jr.] was there preparing for an upcoming fight in Key West. My dad and I, we hadn’t spoken to one another for a year. We had our differences. Two days later, after I brought my brother to the gym, he looks at me and asked, ‘Do you want to try boxing again?’”

________

Nearly a decade after walking away from the sport, Harrison-Lombardi climbed back into the ring ready to resume his amateur career at the age of 27. He started out working with Manfredo Sr., but eventually linked up with Rhode Island-based trainer Brian Pennecchia.

“Peter was busy with Toka [Kahn] and Thomas [Falowo],” Harrison-Lombardi said. “He didn’t have time for me, so Brian took me under his wing,”

Within his first year back in the ring, Harrison-Lombardi won the N.E. Championships in Maine and advanced to the Nationals in Colorado, but his connector flight from Denver to Colorado Springs experienced a layover, so Harrison-Lombardi had to be picked up from the airport and driven to his final destination or else risk missing his fight. When he showed up to weigh in, he was one and a half pounds over the limit, so the fight was cancelled.

“I couldn’t believe I had gone all that way and couldn’t fight,” he said. “I was devastated, but it motivated me. I went back home and kept running and training.”

Through it all, Harrison-Lombardi still smoked a pack and a half of cigarettes a day. He had put most of the last 10 years of his life behind him to chase his dream in the ring, but still clung to a few bad habits along the way.

After two and a half years of competing in the amateurs, including another N.E. Golden Gloves title, Harrison-Lombardi made his professional debut in November of 2012, beating Pubilo Penaby decision, but the thrill was short-lived when the state commission changed it to a no contest after Harrison-Lombardi failed a drug test.

________

The day after his pro debut, Harrison-Lombardi reconnected with a female friend who he hadn’t seen in years. One day, she gave him a bible and told him his journey to stay clean and stay off the streets had to start from within.

He listened.

“It was a major eye-opener for me,” he said. “I was caught up emotionally with everything in my life – my relationship with my father – and this changed the way I started thinking.”

As things began to look up, Harrison-Lombardi hit another roadblock on Valentine’s Day in 2013 when his best friend and roommate died in his sleep in their apartment.

“He drank a lot,” Harrison-Lombardi said. “He had ulcers in his stomach and his doctors told him if he kept drinking he’d eventually drink himself to death. And when he drank, he did drugs.

“No one found him for two days. It made me more depressed. I just did more and more drugs.”

Harrison-Lombardi began spiraling out of control again, dangerously close to losing everything he worked so hard to achieve, until he remembered the advice from his friend who had given him the bible the previous year.

“One day I was staying at a friend’s house and just decided to pray. I said a prayer, and for some reason I suddenly got all this energy. I was so energized, I ran all the way to my mother’s house across town.

“My best friend, he had always told me, ‘You’re good at what you do.’ He told me to stay with it, and I did.

“I’m here now.”

________

Harrison-Lombardi fought four times in 2013 between July and November, twice with CES, and as he prepares to make his 2014 debut, drug-free for the first time in his life, he’s found inspiration not only through his faith, but also through his work helping others outside of the ring.

He’s back with Artwell again, back where it all began at the age of 13 – “I should have never left him,” he admits – and in between counseling and meetings to treat his addictions he’s spending time working with fifth-grade students at the Lillian Feinstein Elementary School in Providence, reading to them at least twice a month.

“Those kids are my inspiration,” he said. “I know I messed up in my life, but if I can help change one kid’s life, it’ll make a difference.

“I have a picture of them they gave me. It’s of all the kids in the class and it says, ‘KJ’s Corner,’ on it. I keep it in the kitchen. Whenever I don’t feel like running, I look at it and it gets me going.”

He’s patched things up with his father, too, thanks in large part to the birth of his sister’s children, which brought the two together after so many years of not speaking to one another.

“We have our ups and down, but it’s more ups than downs lately,” Harrison-Lombardi said. “His intentions were always good.”

Harrison-Lombardi also works part-time as a personal trainer and eventually plans on earning his certification, but for now he’s making one last run at a boxing career, drug-free and off the streets, a long way from that hospital bed.

“This is it for me,” he said. “I’ve beat my body up doing drugs, but I still think I’ve got a good seven years left in me. I’ve got to make the most of it.”